A look back at 2024: our first with season with new tile drainage and our Amigos

A look back at 2025 from Hiram, Morgan and Charles’ iPhones:

If you have been paying attention to farm news, you may have noticed that Nitrogen has become the hot new pollutant, one that governments around the world are clamouring to regulate and restrict. What’s going on with that?

Well, to begin with this deadly pollutant makes up 78% of our atmosphere, and is of course the most significant plant macronutrient. If you’re a farmer or a gardener, you know it makes things grow like crazy. An old timer I know understands it to be called “Nutrigen”, and he’s not far off: it’s got what plants crave.

Early in the 20th century, when there were less than 2 billion people on the planet, the Haber-Bosch process was developed: this allowed mankind to synthesize Ammonia (NH3) from the atmosphere. Since then, the human population has been growing like crazy as well: today 8 billion people rely on synthetic nitrogen for their daily bread.

Unsurprisingly, something as significant as the Haber-Bosch process is energy intensive: it relies on natural gas as it’s fuel source and substrate, and its production releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide (which is the only thing plants love more than nitrogen). So, as you see and hear politicians go on about “nitrogen” this, “fertilizer” that, please understand that they’re really just using Nitrogen as a proxy for their de-carbonification agenda.

The N that Canadian policy makers have in their targets is NO2… yes, laughing gas. Believe it or not, all soils everywhere release NO2 all of the time, and have since time immemorial. Unfortunately, you can’t sniff the air over the dirt and catch a buzz (don’t bother, I’ve tried!) but when farmers apply fertilizer and manure (you know, to grow food for people) the soil releases slightly more of it. Making up a whopping 335 parts per billion of our atmosphere, NO2 is a suspected greenhouse gas.

The current federal *goal* is to reduce NO2 emissions by 30%. Because there is no way that this can possibly be measured, the only way to achieve this arbitrary millstone -sorry- milestone, will be for Canadian farmers to reduce their N use by 30%. And although this program is *voluntary*, it has been suggested that access to AgriStability (crop insurance) will be tied to compliance. The only way we could make Canadian food more expensive, and Canadian farms less competitive would be if we added some sort of new, progressively increasing tax to all of the fuel that farmers use…. oh wait.

The part that should have you most worried about the war on Nitrogen though, is that it is an attack on the very essence of life.

Nitrogen is such a significant nutrient because our friend ammonia (NH3) forms the basis of all of the Amino Acids. I apologize for repeating Grade 12 biology to you, but amino acids are what proteins are made out of. This is, for instance, why leguminous, nitrogen fixing crops (alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, soy, etc.) tend to have such high protein contents.

Proteins are composed of long strings of aminos, and their various charges fold them up in dizzying ways to make all of nature work. As a familiar example, Hemoglobin: the protein in our blood that moves and exchanges oxygen and carbon dioxide throughout the cells of our body to our lungs, is made up of four Polypeptide Chains totaling 574 (ammonia-based) Amino Acids.

So how do these chains get made? This is where is gets really amazing… The information that is translated into these proteins is our DNA. Our genetic code is the blueprint for the length and order of all of these sequences. What we refer to as a Gene is the instructions for linking amino acids into a specific protein. We don’t even know how many genes we have, but it is tens of thousands, and they are all found in our DNA.

To put it more simply, and to put it in context of fertilizer: our bodies, – not to mention bacteria, birch trees, bald eagles and belugas – we are all essentially Ammonia 3D Printers. This is the essence and structure of all life. Far from being a pollutant, Nitrogen is the material God has apparently chosen to express and manifest His wisdom – I would be very suspect of anyone who tries to withhold it from you.

A year in review from Morgan’s iPhone

I hope you are enjoying the gloom of late fall, and powering through it by preparing for holiday festivities and visits with loved ones. It’s strange to think that in less than a month the days will be getting longer again – so, much to celebrate!

This time of year, where we aren’t quite at winter yet – but it’s miserable out – is challenging to get motivated to face the mud. I wonder what our ancestors occupied themselves with at this time of year? In Britain, this time of year was dedicated to “H&D”: hedging and ditching. Where ditches and drains were improved and maintained and the traditional “fences” of the landscape were “laid” and made stock tight. You can watch this film from 1942 to witness the process.

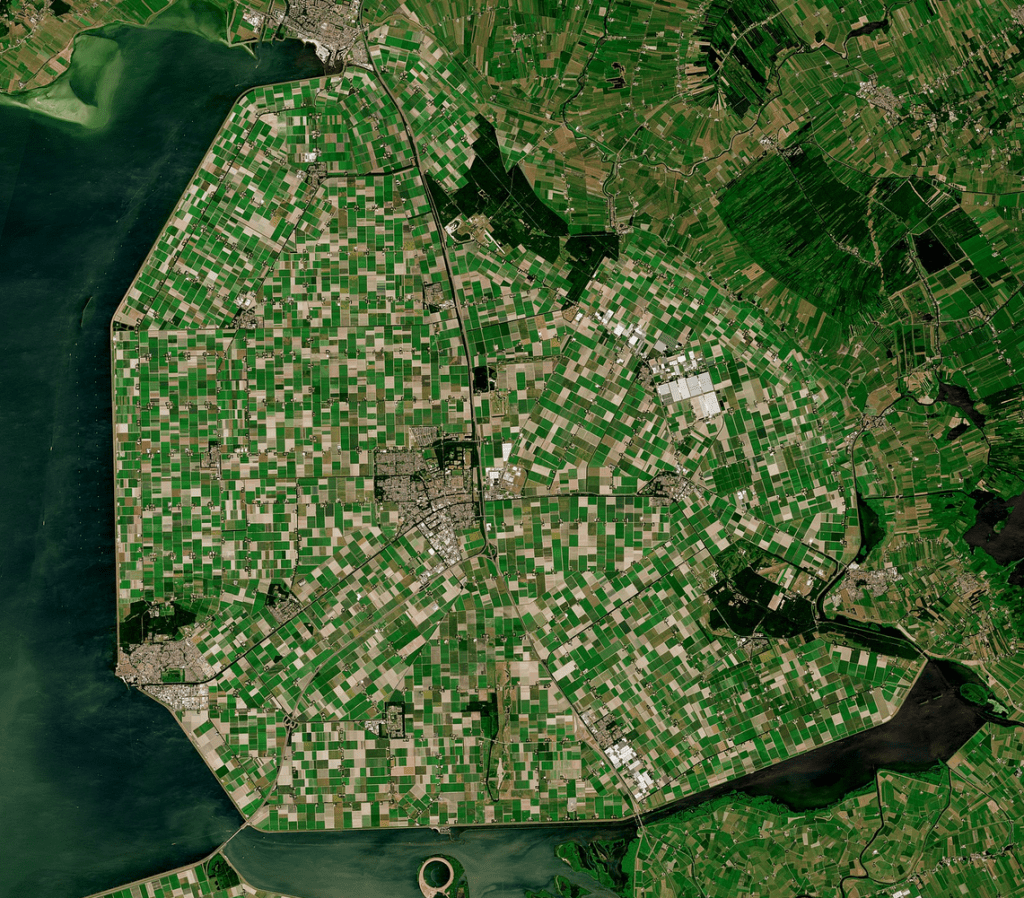

I wonder what my Dutch ancestors did on the first day of December? Perhaps they carved themselves a new pair of clogs – the pre modern version of the rubber boot, and the footwear of choice in a wet, muddy land. Today farmers in Holland are probably preoccupied with recent news that the government will be using eminent domain to forcibly purchase and close upwards of three thousand farms in the name of environmental protection. The European Union has imposed limits on nitrogen run off and reverting these productive farms to nature is the Galaxy Brain solution in this case. That this needed food production will simply occur somewhere else doesn’t seem to factor into these decisions – which is unfortunate because Dutch farmers do more with less than anyone – some of the most innovative and efficient farmers in the world.

Having never learned to speak Dutch, it has been difficult for me to get to the bottom of this issue, everything being poorly articulated second hand by English media. For instance, just finding out how many farms there are in Holland is tricky – I see numbers ranging from 10,000-70,000 (I think the distinction may be between farm businesses and actual plots of land). Whatever it is, 3,000 is a significant chunk of it, and it’s not as though this is being done for the sake of “doing” anything but rather being allowed to revert to “nature” which is a bit of a stretch, considering The Netherlands is probably the most un-“natural” country in the world.

The saying goes that “God made the world, but the Dutch made Holland.” And this is largely true. Half of the country is less than a yard above sea level and a quarter of it used to be under water. Formerly a treacherous marsh – a constantly shifting delta where three major rivers, the Rhine, the Meuse and the Scheldt enter the North Sea – the Dutch have gradually tamed the fertile land and believe it or not, despite being a tiny country with the second highest population density in Europe, are the world’s second largest agricultural exporter by value (after the USA). It really is remarkable what they accomplish.

This legislation was preceded by months of protests, but popular support and international attention were not enough to sway the directives of the wonks in Brussels, and so we are going to witness a significant reduction in Holland’s agricultural output. The protests were remarkable, not only in their scope, but more to the extent that *you were able to get Dutch people to stop working*. A peaceful, orderly sort, it’s not easy to pull a boer off of his polder and the common message was “there is no future here if this comes to pass”. So, I highly doubt these soon to be landless farmers will stick around very long. The government is offering them 120% of the value of their farm and being stubborn farmers, “wooden shoes, wooden head, wouldn’t listen”, will take the money and set up shop where they are appreciated. The exodus of Dutch farmers is nothing new: Canada has been very much blessed by them for the better part of a century.

Unfortunately those same Dutch farmers will face similar regulatory hurdles here in Canada where over the summer the federal government resolved their intention to reduce agricultural nitrogen *emissions* (not run off) by 30%. Well, what are nitrogen emissions and why are we trying to limit them? In this case the molecule in question is N2O (yes, laughing gas), and although it is released naturally by soils everywhere, it is considered a greenhouse gas and the use of manure and fertilizer can increase what occurs naturally.

The government has made a point to emphasize this is a goal, not a law limiting access to fertilizer. What is vexing about this though, is that unlike nitrogen runoff (which can at least be tested with a water sample), there is no way to actually *measure* nitrogen emissions on a farm, and so the entire exercise becomes model-based and the only way to “achieve” it would be to reduce fertilizer use by 30%. Given that nitrogen is the most important plant nutrient (after the carbon they draw from the atmosphere) this would have devastating effects on yields. You think food is expensive now? Most worryingly, it has been suggested that these goals will be “incentivized” by tying compliance with access to Agristability: crop insurance. So don’t worry folks! It’s just a goal! Totally voluntary! It’s not like we will make it impossible for you to conduct business without compliance!

There are two presuppositions I object to in both of these cases: 1) that farmers are willfully polluting and 2) that we would be better off with less farming.

Outside of nitrogen being an extremely important plant nutrient, it is also very expensive (produced with natural gas in the Haber-Bosch process). Farmers, cheap in the first place, are also business people, and so don’t have any interest in losing nitrogen to waterways or the atmosphere. (Farmer’s wouldn’t use any nitrogen at all if they could get away with it!) There are now 8 billion people and counting on planet earth, and we can largely thank/blame synthetic nitrogen for that.

Humanity has become such a juggernaut and our lives so insulated and removed from nature, we forget that we are part of nature as well. And so as much as I appreciate a productive and human stewarded landscape, I can understand the impulse to “rewild” or preserve natural spaces. Taking existing farmland out of production will not accomplish that. There are only more mouths to feed, and the crops that were grown there before will go on to replace some nature elsewhere.

When you have such a manipulated, terraformed countryside as Holland, and given its incredible productivity, why take that land out of production? They literally built a country for intensive farming. Similarly, if you’re a Canadian farmer, why take measures that would reduce your yields by 30%? It’s not that the need or demand for food has gone down. You’ll just have to plant 30% more land (and use that many more resources to do so). In fact, when food prices are high and supply chains are disrupted, why would we grow *less* food? These seem like self defeating measures, and in practice, they are.

On March 2 of this year, on the eve of the growing season, Canada slapped a 35% tariff on Russian imports, which includes 90% of the nitrogen fertilizer in Eastern Canada. To be clear, Russian fertilizer manufacturers did not pay this: Canadian farmers (and later, consumers) did. What was accomplished here? Even if we were to give those in charge the benefit of the doubt and presume these measures are well intentioned, the obviously flawed logic and the openly hostile, top down approach to the industry they are regulating suggest these people at the very least, are not qualified.

At this point, you might be like “Wow I’m surprised Charles is so supportive of all of this industrial agriculture”. Well yes, it’s not my cup of tea, nor what I would want to do personally with a large landbase and lots of money… but I am also a fan of our current standard of living, and the accessibility of food. Measures that will restrict and limit food production means that it becomes scarce and expensive, and the poor are the ones who are going to suffer for it.

I honestly think the significant problems of our global industrial food system are most acutely social, cultural, economic – spiritual – even. Part of why I advocate for the resurrection of a local food system is that I feel people need dignified work, doing something with their hands, and to relate to the world around them – in fields, greenhouses, bakeries and butcher shops. There is actually less land in agriculture today than there was 100 years ago, and at no time has farming been more regulated or resources more carefully handled. The last thing farmers need is more regulation – let alone seizing farms or restricting their productivity.

The weaknesses of global supply chains have been laid bare at this point, and we need to be flexible and allow individuals and communities to chart their own paths. At the end of the day, those Dutch farmers are going to be ok – they looked at a swamp and thought “let’s make this one of the most prosperous places in the world”, and they did – they will figure this out. We could learn something from that perspective.

I hope that you’re taking advantage of the final weeks of summer and enjoying all of the tasty delicacies we’re blessed with this time of year. We’re pretty much over the hump with work finally, and have done nearly all we can for our crops at this point. We can now let the gardens “lay by” for the most part and wait on harvest. “Lay by” is an old expression I first encountered in the Laura Ingalls Wilder’s book Farmer Boy.

Although best known for Little House on the Prairie, Ingalls’ Farmer Boy documents a year in Laura’s husband’s childhood on a farm in upstate New York in the mid 19th century. Outside of being sweetly entertaining and beautifully written and illustrated, like the rest of the Little House series, Farmer Boy is particularly interesting because it is set across the St. Lawrence not far from us. A mixed farm of cattle, sheep, horses, swine, fowl and crops, the novel provides a very detailed account of what farm life would have looked like here at the time of Confederation.

When you reach this stage of the year in the book, Almanzo’s parents have enough breathing room that they go on a week-long journey to visit some loved ones and leave the children behind to care for things. Naturally the children get into all sorts of mischief, not to mention making as much ice cream as they like and eating melons all day every day. Our children’s daily melon consumption seems to be approaching their own body weight at this point in the summer, proving as always, that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Letting crops “lay by” can be a little bit frustrating, because I always want to “do something” to swing odds in our favour. But there is only so much that can be done. When I first started farming my mother often quipped that I was crazy to do something that so heavily hinged on the vagaries of the weather. I didn’t really notice at the time how right she was: when you are just learning, there is so much in motion that you don’t really see how everything is being affected. But at this point in my career, it is challenging not to directly tie my mood and outlook to weather conditions: they are that critical.

So, we go from high stress, blistering 30c+ dry heat, to mild, sopping wet 99% humidity. The plants can relax, but pathogens love it, and you can watch diseases spread by the hour under these circumstances. It is normal and expected this time of year: just sometimes a bit hard to watch. A few days, and even a few hours of extreme weather can have profound impacts on crop development: plants really are these hardwired environmental feedback machines. Now it’s one thing to note all of this in our gardens, but weather trends actually play a huge role in the business of agriculture.

Futures trading in agricultural commodities is a giant business (which many farmers also engage in) and weather patterns in major grain producing regions around the globe directly impact these prices, which can swing dramatically by the hour. Data released by the USDA regarding planting, crop conditions and expected yields will directly affect the price of a loaf of bread: and these crops have not even been harvested yet!

Right now there is an event called the Pro Farmer Tour, where crops are being sampled across the US Corn Belt with an eye to predicting yields in the fall. From what I’ve seen on Twitter, things are looking less stellar than hoped for. The silver lining to information like this, of course, is that poor crops means high prices – and they were record high to begin with! This is good news to farmers in our area (which is really a tiny, marginal outpost in the world of commodities), because, as you may notice, the field crops in our area are looking pretty mint.

I can only get so excited about the success of industrial export corn and soybean crops, however. Although they represent continued cashflow for the farmers who persist in our area, the real wealth they generate largely is made elsewhere: by the companies who supply the inputs to grow them, and the companies who actually process these products into their final form (often one and the same). It becomes quite stark when you compare it to Farmer Boy…

Almanzo’s family produced not only crops for direct human consumption, like wheat and potatoes, but also dairied: separating milk to make butter for sale, and value-adding the byproducts by feeding the skim to pigs and calves. The farm also produced and sold means of transportation and traction (raising and breaking horses and oxen), as well as the energy/fuel they required (hay and oats). And if all that wasn’t impressive enough, they produced the raw material for textiles as well: shearing sheep for fleece to be sent off and carded, spun and woven at a mill just like the one on the Cataraqui.

So, we go from farms operating as dynamic organisms: feeding, moving and clothing their communities, to farms acting as substrates for industrial chemical conversion. It’s hard to say which system is more “sophisticated” but it’s very clear which is more aesthetically pleasing and which generated and retained more wealth in our communities. The Woolen Mill itself is a great analogy for this transformation when you observe what businesses it contains now: we went from controlling the means of production to put clothes on our backs, to offshoring it to the third world, and traded it for an economy of recreation, restaurants, spas, media and professionals. Ostensibly this took place in the name of Efficiency, but when you learn of the absurdity that Ontario sheep producers shear their flocks at a loss (it costs more to remove the wool than the wool itself is worth) it is hard to accept that any of this is actually sensible.

When you take this model of efficiency to its logical conclusion, things get pretty grim. London, Ontario is now home to the world’s largest cricket factory. Producing 28 millions of pounds of crickets per year, the plant was subsidized by the federal government and although due to lack of demand most of the output is being directed into pet food, the entire project is couched in feel good language around food security.

Founder, Mohammed Ashour: “We have a massive growth in both population and appetite for protein, while at the same time we’re seeing a significant reduction in arable land and resources to produce food. Our longer-term vision is to make sure that this is a protein source that can be available and affordable to genuinely address food insecurity in many countries around the world.”

Egghead from University of Guelph, Evan Fraser: “I think it is so exciting that we are at a moment in history where we’re really re-evaluating our food systems in general, and exploring new ways of exploring protein and more efficient ways of producing protein.”

Here’s the funny part, though. Guess what the crickets are eating? CORN AND SOYBEANS

You can watch this video from Entomo Farms in Norwood, Ontario and observe for yourself.

So when you hear our central planners talk about “food security”, know that they’re not talking about changing the food system or blanketing the landscape in diverse Farmer Boy style family farms. They’re talking about reinforcing the current industrial paradigm, all of which effectively erases local distinctions, and is ultimately dehumanizing in the way that it removes us from our environment and the people that make up the systems that support us. I am really grateful for all of you taking the time to work with our farm, and not letting your eating habits “lay by”, but rather deliberately working towards the type of diet you can savour and the type of world you want to leave for your children.

It looks like our balmy fall is over. We had a good run, didn’t we? With snow in the forecast and a projected high of 0 for Saturday, we will no longer be operating our stand on Highway 2 and resuming home deliveries for the season. Thanks so much to all of you – it was our best year yet! Please don’t be shy to get in touch via phone or email, or utilize our online store.

We had some nighttime lows down to -8 last night so it’s likely that most of our remaining field veggies are done for the season. We will inspect when things thaw out. There were still plenty of crops out there – even a small fortune in lettuce.

I’m sure you’ve heard about the current lettuce shortage – prices have tripled and a pack of romaine hearts is over $12 at our little country grocer. Restaurants across North America have begun warning that it may not be featured on their menus and retailers are limiting purchases. Fortunately, although it is a staple, and very pleasant, it is essentially nutritionally inert, and we will all be fine without lettuce for a spell. If you crave the crunch, don’t worry, there’s plenty coming: it takes only two months to grow a head of it.

But why isn’t there any on the shelves right now? Well, because pretty much all of the lettuce in North America comes from one place at any given time and it’s done poorly there lately. At this point you’re probably saying… “Wait, you’re telling me the whole crop comes from a single county? Like they don’t sort of spread the risk out and grow some in, say, South Carolina, or the Comox Valley?” Yes, that is actually the case: that we can have lettuce in the field here in Ontario (at least until last night) but not on the shelf… is indeed how the industry works.

I’ve written a bit about why they grow all of that lettuce in the southwest, (largely a mix of sunlight and labour)… but this sort of specialization/optimization is standard operating procedure with pretty much every article of commerce. We’re seeing this right now with the collapsed supply of children’s pain medications: we simply don’t make any here. The precursor for Children’s Tylenol, Paracetamol, apparently all comes from India.

This stuff could probably be made by any competent chemist… I actually think the time has come for a Canadian version of Breaking Bad, where a rogue technician at Queen’s teams up with a struggling student to produce black market Children’s Tylenol, quickly coming to overthrow the leader of the Hell’s Angels and dominate Canadian organized crime… So far I haven’t heard back from any studios!

What’s vexing about these situations is how avoidable they are. Lettuce is not hard to grow – this is not like the microchip shortage. Acetaminophen is a cheap, simple, generic drug that has existed for over 100 years. That Canada cannot start cranking it out within days if need be is a huge indictment of the overly regulated, overly specialized, top heavy approach to securing basic necessities.

The same can be said for diesel fuel. High diesel prices are a huge factor in our ever decreasing buying power. Because it literally makes the world go ’round, its price is built into everything. There’s not enough to go around and so it gets more and more expensive….

Canada has the third largest petroleum reserves in the world, and given the vast and frigid nature of our country, you’d think we would be eager to simply produce more here. Something I’ve heard my entire life is “Yes Canada has lots of oil, but what we lack is refining capacity.” As though refining oil was this really magical process that you need some rare set of circumstances in order to accomplish. When diesel jumped last spring, curiosity got the better of me and I asked “how do they make this stuff anyways?” Well, it turns out you don’t actually need fairies or wizards or a secret password. IT’S MOONSHINING

You literally heat up crude oil until it evaporates then condense the vapours at various temperatures, creating the different grades of petroleum products we rely on. “Ohh no no Charles, it’s much more complicated than that!” Ok, tell that to these gentlemen in Nigeria, or these intrepid entrepreneurs in Syria. If these are a little bit rough for your tastes, perhaps you might be interested in going in with me on this small scale oil refinery, available for sale on Alibaba.

Now, of course, Canada’s oil is largely locked up in the tar sands, which adds an additional process and expense to securing crude. One of the more novel approaches to solving this problem was originally known as “Project Cauldron” – which involved detonating hundreds of nuclear warheads under the Athabasca oil patch to heat and liquify the bitumen for conventional extraction. Although later christened with “a less effervescent name” for the sake of public consumption, for better or worse, the project never came to pass. The idea is evocative of a not so long ago era of when “what if we blow it up”? was a common public policy approach to various problems. I highly recommend this 1970 news segment documenting the use of explosives to deal with the problem of a beached whale, and the unintended consequences of the “blow it up” approach.

And so while we hopefully will not have to rely on the experimental use of nuclear weapons, it’s becoming clear that the hyper specialized and hyper regulated world we have created, for all of its efficiencies, has its limitations. Seemingly simple things we perfected 100 years ago – like having lettuce out of season, making simple medications, and generating affordable fuel – are now becoming impossible, and if we continue down this path, we will end up like the barbarians, where after the fall of Rome, when as the aqueducts began to fail, there was no one left who knew how to repair them.

So, I appreciate you working with our inefficient, unspecialized little farm. Not only is it a hedge against The Leviathan, but I hope it is also much more pleasant and humane than being herded like cattle through the Costco. The above image, by the way, is of 19th century Paris market gardeners, growing lettuce in the wintertime. There is nothing new under the sun.

I’d really like to thank everyone that came out to our first week down on Highway 2. It was well worth our effort and it was wonderful to see old and new faces. We also appreciate those of you who are taking advantage of our online store – and please don’t be shy if you just want to do things the old fashioned way and just give us a ring.

We’ll be back again on Saturday rain or shine and hope for slightly better weather than last week and just in general for this season. By this point in late April, farmers would like to be in full swing: spreading manure, working the land and getting crops in. There was a small amount of activity the last couple days in our area, but after last night’s soaking everything will be parked again for at least several more days on even the highest and driest land.

Here in Ontario we hope for a bit of a drought in the spring: it lets fieldwork and planting get done uninterrupted and also makes life a little nicer for the cattle which are being turned out – not to mention their calves… There’s a saying in farming that “a dry year will scare you – a wet year can kill you” – this sounds a bit counterintuitive but also points to a lot of why things are done the way they are in agriculture.

For instance, that most produce in North America is grown in the deserts of California, Arizona and Texas seems ridiculous when you first consider it – having to divert all of that water all that way when the crops could just be grown where the water originates. However, the aspects of precise control of water, and the extremely low ambient humidity makes the desert a much more “controlled environment” to grow delicate, high value crops. You need an inch of rain? Turn on the tap. You need to get equipment or harvesters into the field? Turn it off. There are no fungal problems and the barren landscape provides no alternative host for pests and diseases. And this is why lettuce (an extremely thirsty, delicate crop) is a billion dollar industry in… Arizona of all places.

And so while Arizona might dominate the winter lettuce trade, the trend continues northward up the Pacific coast and mountain valleys. Whether the Central and Salinas valleys, the Willamette in Oregon, or the rainshadow of the Cascades in Washington, they make the desert bloom with irrigation, producing high value crops ranging from wine grapes, to apples, to Walla Walla onions, to grass seed. A migrant Central American labour force also happens to follow this trend north and south with the seasons but that is something for another article.

Even in Canada, in the northernmost tip of the Great Sonoran desert: the arid Osoyoos Valley in British Columbia, stone fruit orchards and vineyards thrive where homeowners don’t really need a lawnmower. Such are the advantages of a desert climate when it comes to growing dainty crops.

Dry conditions are not only advantageous for horticulture, but it is no coincidence that the cattle industry tends to be centered in drier regions as well. Quite simply, looking after large amounts 1000lb+ animals is just a lot easier when there is no mud. It is wet and cold and uncomfortable for the cattle, a potential death trap for calves, and a great way to mire and destroy farm equipment. It is also why traditional cattle husbandry in this region is very “barn centred” and the only extensive “range” type beef operations in these parts are possible on very rocky or sandy ground.

At the moment, our beef cattle have some rocky hills to climb up onto and fortunately aren’t yet due to calve. Our hens have dry, elevated homes on wheels to sleep and lay in, but we’ve essentially had to sacrifice an area for them to debauch during the daytime, this wet spring – rather than constantly moving them about, to only extend that effect to more areas. The longer I raise livestock, the more I understand why farmers tend to want to just stick them in a building…

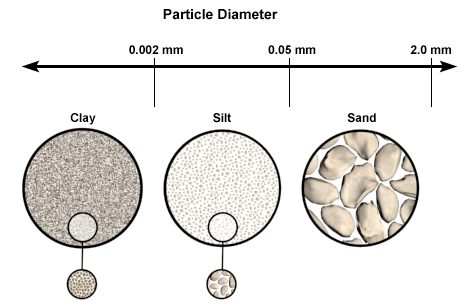

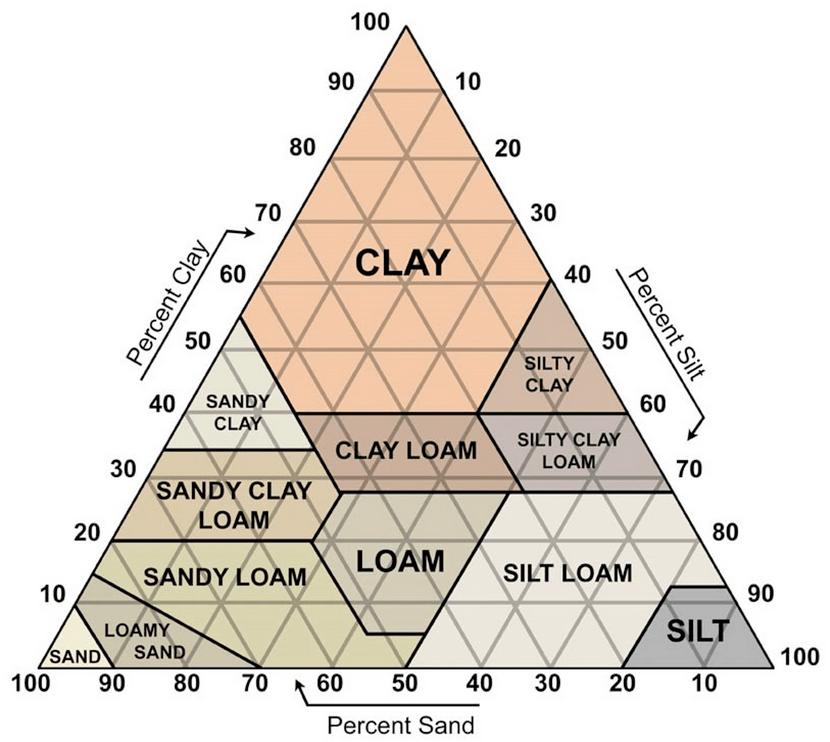

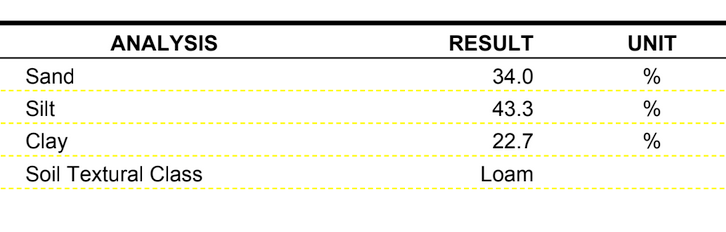

The closest thing produce growers in this area can do to approximate the “desert effect” is to grow their crops on sand. Sand is referred to as a “light” soil and is great because it warms up quickly in the spring, and unless the water table itself is high, is freely draining, meaning that farmers can get back on the land quickly after rains to till, spray, harvest etc. The problem with sand is that it is droughty, and lacking the particle surface area of “heavy” soils to hold nutrients, tend to be infertile and acidic.

Heavy clay soils can hold onto a great deal of nutrients and moisture, but can be very tricky to till and plant into, warm up very slowly and are prone to compaction and poor drainage. The “just right” and most desired soil type, in theory at least, is “Loam”, and according to our soil tests this is what we have here. Our gardens were formed on the bottom of a shallow, warm lake some 10,000 years ago, and not only do we have a nice balance of soil particles, but a great deal of calcium and organic matter as well.

Organic matter, “humus”, is the real life blood of a living soil and helps ameliorate the deficiencies of any sort of dirt: making sands more moisture retentive, clays more friable and so on. You maintain and build organic matter with cover crops, compost and manure: we’ve got lots of black gold on hand here – we just need some strong winds and bright sun to hang around so we can get it spread on the land. It always comes along… eventually.

Thanks so much to all of you who continue to come out to the Highway 2 farmstand! Suzanne is officially off for the season, so we will be manning the stand ourselves for what’s left of the year; we’ll be going on a week by week basis, and given the mild temperatures, WE WILL be there this coming Saturday. Thanks as well for all of you who took advantage of our potato deal: it will be continuing. $20 for a bushel of field run, unwashed white or red potatoes – please bring your own containers/bags and we’d appreciate you letting us know so that we bring enough.

A lot of you asked how to store potatoes. Well first of all, they should be kept in the dark. They turn green in the light (they’re still alive after all) and any green spots you ever see on potatoes should be peeled off: it will give you indigestion. After that, a steady temperature is helpful, ideally about 4 degrees. For most of you this will be against the warm wall in your garage or mudroom or perhaps in an unheated part of your basement. We will be selling potatoes over the winter in smaller portions as well, but given the extra handling the prices aren’t going to be so hot, so clearing out a corner to tuck these away will be well worth it.

Another interesting aspect of focusing on potatoes a little bit is that we get a lot of feedback from our customers about our potatoes. Overwhelmingly, you point out that our potatoes are *much different* than what you’re used to getting at the grocery store – often we hear that they are much “firmer” and that they take twice as long to cook… What does this mean?

I’m not quite sure, although regardless I am glad to hear that you are enjoying them. I don’t know if it is anything we are doing in particular, or that we are growing special varieties or anything (we grow very “mainstream” potato cultivars). If I had to guess, it would be that we don’t really do any crop protection with our potatoes other than an organic spray for Colorado Potato Beetles for our early crop, and sort of let them just grow… and die (which they do rather quickly thanks to a multitude of diseases they are subject to). This runs rather contrary to industry standards: potatoes are one of the most medicated crops grown in Canada, treated heavily from the day of planting onwards. This means incredible yields of potatoes – easily double and even triple what we produce on our farm, but also a sort of “puffy” crop that did not have to contend with the gauntlet of nature on its own. Perhaps most disconcerting about this is that the insecticides and fungicides they rely on to do this are systemic… which is to say that they don’t simply lie on the surface of the leaf or seed potato, but are actually absorbed and integral to the plant itself (which is why they work so well). You can read about one such product Movento, from Bayer: the world’s largest agribusiness and pharmaceutical company.

I want to make clear to you though, that the reason a potato farmer does this is not because he is dishonest, bent on making you sick or doesn’t care. It’s economics. He has a lot of very expensive land and equipment to pay for, and the only way to do this is by growing as much potatoes as possible. We are all subject to larger forces, and he is told this is the only way; but I am going off on a tangent…

This question of what makes food “good” is currently what is simmering away on the burner in the back of my mind. It’s certainly distinct but very hard to define. Especially when you look at something as homely and bland as a potato… like how can there really be that much of a difference? When I occasionally peruse the produce section of the grocery store, I am often astounded at the condition of the produce and that a manager actually displayed that stuff with a straight face – or that anyone would think to buy it.

I believe that this lies at the heart of why so many of us find it hard to get excited about cooking: the raw ingredients are often uninspiring to say the least – even just to make a sandwich. Take another bland, starchy staple like bread. It is extremely difficult to find good bread (nor is it cheap when you find it) – out here in the sticks it simply does not exist. In the rural grocery store you have either parbaked bread full of sugar and oil, or mysterious products like Wonderbread, which really represent this ideal of the modern era; wherein we take something as simple and perfect as bread, and try to transform it into an idealized, homogenous, universal, shelf stable facsimile of a product which needed no improvement.

There may be no more divine food than fresh bread, and the main “problem” with bread, of course, is that it goes stale. This is solved quite simply by eating it and buying more. If that’s too much, we can do things like make french toast, bread pudding, or crostini. Alternatively, sourdough bread resists staleness owing to the rich microbial goop that covers the strands of gluten, but it is more expensive to produce given the prep times and more elusively, the skills needed to make it.

Products like Wonderbread, along so much of the modern culinary landscape, is a rejection and (failed) transcendence of basic physical reality. Bread goes stale, fruit is seasonal, meat and eggs are expensive to produce. Blights kill potatoes, you need talented people to make good food, and a just in time global food system is really efficient… until it isn’t.

I like to make shepherd’s pie. It’s a great dish for winter when I actually have time to cook and it’s something, other than the worcheshire sauce, I can make entirely with ingredients from our farm in the middle of winter: potatoes, hamburger, onions, garlic and carrots. Just how you prepare this mix of very simple ingredients can produce quite different results. I don’t try to embellish it too much, just a steady pursuit of the Platonic Ideal of shepherd’s pie: how the meat is browned, how the potatoes are mashed and spread, how much “crust” you put on it in the oven…

Outside of oven temperature, the most important variable here may be our intent. Am I paying attention? How do I feel about the eaters of this meal? Am I thankful for my daily bread? The answers to these questions will largely inform how we approach our food: both from a practical standpoint in terms of how much we can be bothered to learn about our ingredients and refine our techniques, but more importantly, how much we enjoy the meal itself (and the company we share it with).

Julia Child’s seminal Mastering the Art of French Cooking, whose dedication reads:

To La Belle France

WHOSE PEASANTS, FISHERMEN, HOUSEWIVES,

AND PRINCES – NOT TO MENTION HER CHEFS –

THROUGH GENERATIONS OF INVENTIVE AND

LOVING CONCENTRATION HAVE CREATED ONE

OF THE WORLD’S GREAT ARTS

is a must if you are interested in this careful and thoughtful handling of simple ingredients. From the foreword:

Pay close attention to what you are doing while you work, for precision in small details can make the difference between passable cooking and fine food… You may be slow and clumsy at first, but with practice you will pick up speed and style.

Allow yourself plenty of time… If you are not an old campaigner, do not plan more than one or complicated recipe for a meal or you will wear yourself out and derive no pleasure from your efforts.

A pot saver is a self hampering cook. Use all the pans, bowls and equipment you need, but soak them in water as soon as you are through with them. Clean up after yourself frequently to avoid confusion.

Train your hands and fingers; they are wonderful instruments. Train yourself also to handle hot food; this will save time. Keep your knives sharp.

Above all, have a good time.

I find it quite telling that most cookbooks and food trends these days are focused on restrictive diets (vegan, keto, carnivore, you name it) and the overcoming of our bodies, or ideological pursuits, rather than *actually cooking food properly* so that you enjoy eating it. It is a measure of this same disconnection from physical reality that produces Wonderbread or horrific products like SQAUREAT (I’m sorry if I am the person to show you this abomination):

What I find funny (and sad) about these sorts of products is the idea that we need to free ourselves from the perceived drudgery of food preparation and proper meals. What exactly is so important that you think you are doing with your time, that you believe eating these pucks is going to give you the edge? I guarantee you that the people to whom this is attractive are extremely physically awkward and very much stuck in their own heads.

Watch Julia Child make an omelette here. You really cannot do that without being present in the flesh, connecting your eyes, mind and hands to a very careful and time sensitive task. You actually have to climb out of your neuroses and use the body God gave you to interact with Creation – also known as Normal Human Life.

We have to eat, we ought to do it as absolutely well as we can. While we’re at it, why not enjoy it and share it with the ones we love? I double dare you to drop $40 on dirty potatoes, stick them in your garage and absolutely perfect scalloped potatoes (or whatever you like) this winter. Observe the differences between the white and red potatoes, notice how they change in character in storage, and play with how you treat and handle them and the way it changes your dish. I mean, what else are you doing?